This blog takes a step back and further defines NAFLD and the associated work we are doing in our current clinical trial (NCT04920058) on non-diabetics. This ongoing research reminded us how ubiquitous this condition is and how it can advance without any overt signs detected in standard bloodwork or other routine exams.

What is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)?

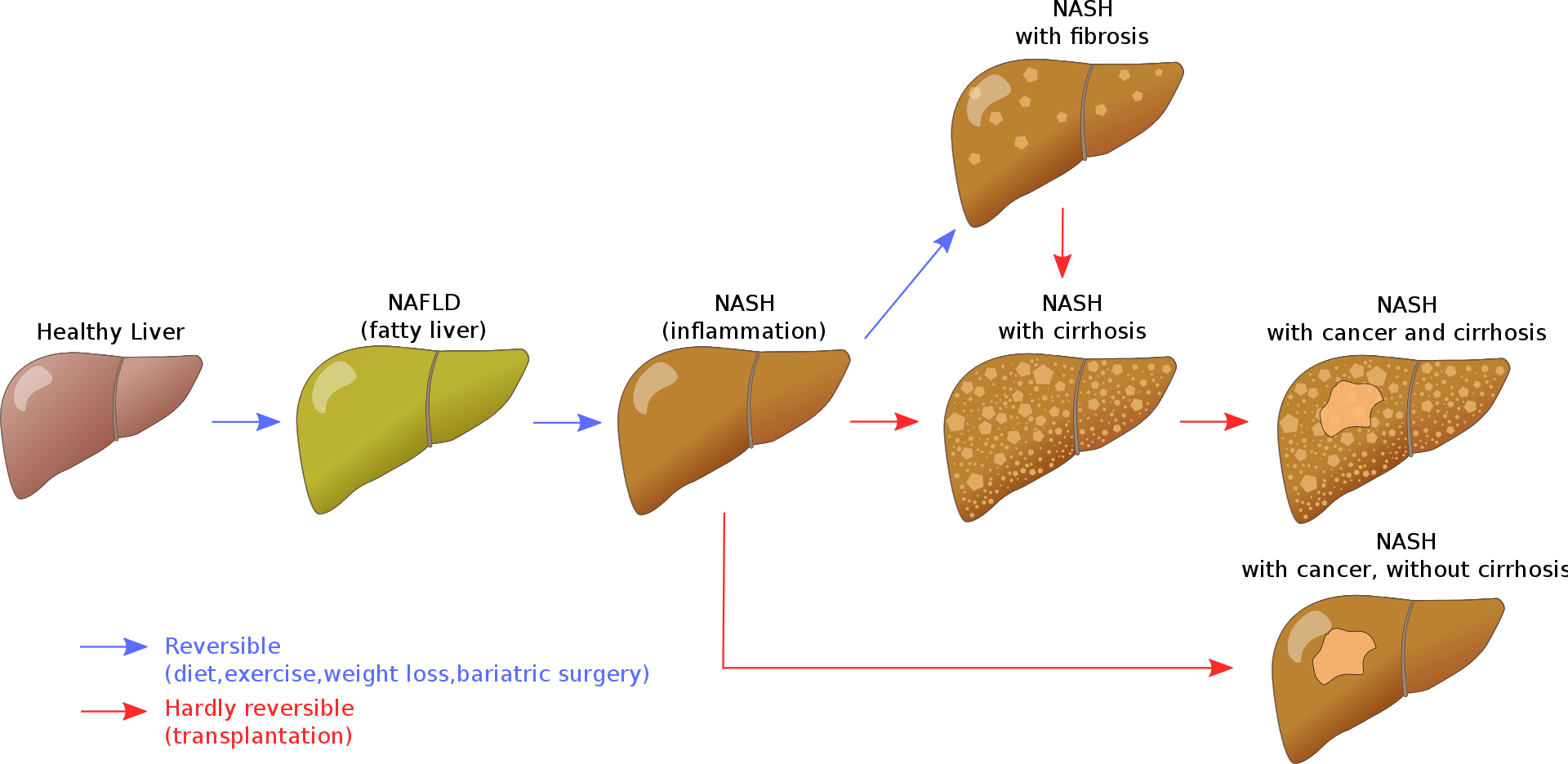

NAFLD is defined by the liver containing more than 5-10% percent of its weight from fat and numerous studies and reviews have defined NAFLD as an emerging health problem. Unfortunately, NAFLD typically causes no overt symptoms during pathological progression to Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH → Fibrosis →Cirrhosis) , so it is truly a silent killer if left untreated. For example, people with NAFLD often have liver enzymes within normal range, although seeing a trend of increasing values over time could be a warning sign. This recent NEJM prospective study (1) demonstrated that patients with more advanced stages of NAFLD (leading to fibrosis) have significantly increased risks of liver-related complications and death (results from NCT01030484).

What is the prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease?

NAFLD is the most common liver disease in industrialized countries. The Dallas Heart Study and the Dionysos Study reported that 30% of the adults in the USA and 25% in Italy have NAFLD, and systematic reviews reveal that 40% of patients with NAFLD will progress to end stage fibrosis (2). NAFLD increases with age, obesity, insulin resistance and poor metabolic health biomarkers. Rates of NAFLD are higher in males (2:1 ratio) and now we are seeing an alarming rise among children. NASH will soon be the number one reason for liver transportation due to our obesity epidemic. In addition, NAFLD increases the risk for liver cancer even in the absence of cirrhosis. Up to 45% of people with NASH without cirrhosis can develop hepatocellular carcinoma (3).

What is the cause of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease?

Variations in several genes may contribute to NAFLD, as well as environmental factors, but lifestyle appears to be the main driver of metabolic derangement that results in NAFLD. As the name implies, this is not caused by excess alcohol, however, alcohol consumption can exacerbate the disease development greatly. NAFLD is caused by defects in fatty acid metabolism that is primarily due to a positive energy balance (usually excess sugar and carbohydrtaes), resulting in fat storage within the liver (4). This is further exacerbated by the consequence of peripheral resistance to insulin, whereby de novo lipogenesis and the transport of fatty acids from adipose tissue to the liver is increased. In other words, insulin resistance triggers fat production and fat storage within the liver. Impairment or inhibition of receptor molecules (PPAR-α, PPAR-γ and SREBP1) that control the enzymes responsible for the oxidation and synthesis of fatty acids appears to contribute to fat accumulation (5). Over time, this fat accumulation creates inflammation through its production of cytokines, progressing the disease to NASH. As the secondary inflammatory process worsens, scarring ensues, developing fibrosis with ultimate development of cirrhosis if this disease process progresses. NAFLD-induced fibrosis at stages F3 and F4 were associated with increased risks of liver-related complications and death (1).

How is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease diagnosed?

The Gold Standard diagnosis of NAFLD is done through a liver biopsy with evaluation of histopathology; however, diagnosis can also be made without an invasive biopsy. As mentioned, elevated liver enzymes are not always seen and not part of routine diagnosis, but NAFLD should be considered in the presence of elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT) when it occurs with obesity, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and elevated triglycerides. Several imaging technologies can accurately diagnosis NAFLD, including Ultrasound (US), Computerized Tomography (CT), or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Compared to histology as a reference standard, the overall sensitivity and specificity of US is high and often used initially when NAFLD is suspected. Ultrasound is far more affordable cost and lacks the radiation exposure associated with CT scans. The grading of liver steatosis (fat) is obtained using US features that include the following (6): Liver brightness, contrast between the liver and the kidney, US appearance of the intrahepatic vessels, liver parenchyma and diaphragm.

- Steatosis is graded as follows:

- Absent (score 0) when the echotexture is normal

- Mild (score 1) when there is slight and diffuse increase in liver echogenicity with normal visualization of the diaphragm and the portal vein

- Moderate (score 2) moderate increase in of liver echogenicity with slightly impaired appearance of the portal vein wall and the diaphragm

- Severe (score 3) marked increase of liver echogenicity with poor to no visualization of the portal vein wall, diaphragm, and posterior part of the right liver lobe

How is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Treated? Is NAFLD Reversible?

The good news is that we can take steps now to diagnose, prevent and reverse NAFLD. Hepatic steatosis is considered reversible and nonprogressive if the underlying cause is reduced or removed. The emerging data in adults (7) and adolescents (8) suggests that excess sugar and processed carbohydrates are the catalyst for hepatic steatosis supports the reasoning to utilize very low carbohydrate/ketogenic nutrition as the primary means for treatment. The common belief that increasing dietary fat intake invariably leads to fatty liver and prevents fat mass loss has been proven wrong by an elegant experiment, showing that a eucaloric high fat ketogenic diet inhibits de novo lipogenesis (fat storage) and induces fatty acid oxidation, leading to weight loss and reduced hepatic fat content (9) Emerging research reveals how the production of ketone bodies through a very low carbohydrate, high fat nutritional plan creates several secondary pathways permitting the healing and resolution of liver steatosis (5).

Ketone bodies in the presence of very low carbohydrate nutrition heal hepatic steatosis through the following mechanisms: (2)

- Reduction of hunger

- Lowering of Blood Glucose

- Lessoning of Insulin Resistance

- Reduction of Visceral Fat

- Alterations in DNA signaling pathways through changes in Histone Acetylation

- Reduction of Oxidative Stress

- Reduction of Inflammatory Cytokines

- Reduction in Pyroptosis, which is a form of cellular death triggered by proinflammatory Blocking this pathway prevents the development of fibrosis.

- Alterations of the Gut Microbiome, which increases the absorption and production of micronutrients such as Folate, further reducing oxidative stress.

If you had not seen our previous KetoNutrition blogs on Ketones and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), be sure to check that out. In addition, it is important to highlight that some evidence reveals increasing fat intake from Omega-3 sources such as fish, shellfish, chia seeds, flax seeds, and walnuts rather than from excess saturated fat will provide even greater outcomes in treatment and resolution in hepatic steatosis (7).

What evidence-based outcomes are we seeing with our Well-Being Tribe members participating in our 12-week program and associated clinical trial (NCT04920058)?

We have seen significant improvements on US imaging and reduction in liver enzymes, which provides evidence of reduced inflammation. To date, our partnered research with Levels Health reveals 62% resolution and 70% improvement in hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) with members completing our program adopting and sustaining very low carbohydrate, moderate protein, high fat nutrition. We often get asked: Will a person will need to maintain very low carbohydrate, high fat nutrition life-long to prevent recurrence of hepatic steatosis? While we do not (yet) have the data to confirm this opinion, we believe the changes in nutrition and metabolic tracking awareness (eg. CGM, etc) will provide long-term benefits in eating behavior. If an individual maintains long-term nutritional changes consuming a diet comprised of real, whole foods, without excess sugar and processed carbohydrates, with an abundance of high-fiber plants, healthy fats, and sufficient protein, it is reasonable to expect persistent resolution of hepatic steatosis along with sustained weight loss maintenance and improved insulin sensitivity.

Written by: Dr. Allison Hull, DO and reviewed by Dominic D’Agostino, PhD

References:

- Sanyal, A. J., Van Natta, M. L., Clark, J., Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A., Diehl, A., Dasarathy, S., Loomba, R., Chalasani, N., Kowdley, K., Hameed, B., Wilson, L. A., Yates, K. P., Belt, P., Lazo, M., Kleiner, D. E., Behling, C., Tonascia, J., & NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN) (2021). Prospective Study of Outcomes in Adults with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385(17), 1559–1569. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2029349

- Do A, Lim JK. Epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A primer. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016;7(5):106-108. Published 2016 May 27. doi:10.1002/cld.547

- Watanabe M, Tozzi R, Risi R, Tuccinardi D, Mariani S, Basciani S, Spera G, Lubrano C, Gnessi L. Beneficial effects of the ketogenic diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A comprehensive review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2020 Aug;21(8):e13024. doi: 10.1111/obr.13024. Epub 2020 Mar 24. PMID: 32207237; PMCID: PMC7379247.

- Reddy JK, Rao MS (May 2006). “Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation”. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 290(5): G852-8. doi:1152/ajpgi.00521.2005. PMID 16603729.

- Lundsgaard AM, Holm JB, Sjoberg KA, et al. Mechanisms preserving insulin action during high dietary fat intake. Cell Metab. 2019;29(1):50‐63 e4.

- Ferraioli G, Soares Monteiro LB. Ultrasound-based techniques for the diagnosis of liver steatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct 28;25(40):6053-6062. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i40.6053. PMID: 31686762; PMCID: PMC6824276.

- Noakes, T. D., & Windt, J. (2017). Evidence that supports the prescription of low-carbohydrate high-fat diets: a narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096491

- Schwimmer, J. B., Ugalde-Nicalo, P., Welsh, J. A., Angeles, J. E., Cordero, M., Harlow, K. E., Alazraki, A., Durelle, J., Knight-Scott, J., Newton, K. P., Cleeton, R., Knott, C., Konomi, J., Middleton, M. S., Travers, C., Sirlin, C. B., Hernandez, A., Sekkarie, A., McCracken, C., & Vos, M. B. (2019). Effect of a Low Free Sugar Diet vs Usual Diet on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adolescent Boys: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 321(3), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.20579

- Ipsen DH, Lykkesfeldt J, Tveden-Nyborg P. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(18):3313-3327. doi:10.1007/s00018-018-2860-6

- Lee CH, Fu Y, Yang SJ, Chi CC. Effects of Omega-3 PUFA Supplementation on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020 Sep11