Last month a study regarding intermittent fasting published in JAMA Internal Medicine gained a lot of attention on social media, even catching the eyes of larger news outlets, like the New York Times and CNBC.

The study was designed to test the effects of time-restricted eating (TRE*) on weight loss and metabolic health in patients with overweight and obesity.

TRE is a form of daily intermittent fasting that restricts food intake to 12-hours or less.

In this particular study, the popular “16/8” schedule was used, meaning participants were to eat within an 8-hour window and fast for the remaining 16. The chosen eating window was 12 pm to 8 pm, based on what was likely to fit within most lifestyles, with dinner typically being the most social meal of the day.

Here’s an overview of the study design:

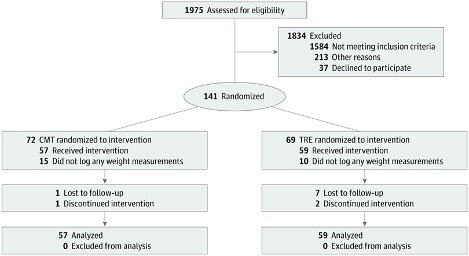

141 participants were randomized into one of two groups to follow for 12-weeks:

Source: Lowe et al., 2020.

Group 1. TRE: These participants were told to eat ad libitum (as much as they want), but only within the hours of 12 pm to 8 pm. Outside of the eating window, they were allowed to consume non-caloric beverages such as black coffee or tea.

OR

Group 2. CMT (Consistent Meal Timing; acted as control): These participants were told to eat three structured meals per day (6 am to 10 pm*), with snacks in between as they desired.

*An issue worth pointing out with the CMT group is that meal 1 was to be eaten between 6 am – 11 am, meal 2: 11 am – 3 pm, and meal 3: 4 pm – 10 pm. This introduces considerable variance in the CMT’s eating window, with the most condensed being just before 11 am to just after 4 pm and the most extended being just after 6 am to just before 10 pm.

What or how much the participants ate was not controlled for in either group. In other words, they could eat as much as they wanted so long as it fit within the study’s time constraints.

Each participant was given a digital Bluetooth scale to track their weight daily. Through a mobile app, they were also to complete a survey each morning that tracked adherence. The survey asked: “Did you adhere to your eating plan on the previous day?” The results of this question were used to measure compliance.

The primary outcome measure of the study was weight loss.

By the end of the 12-weeks, both groups lost weight. On average, the CMT group lost ~1.5 lbs, and the TRE group lost ~2 lbs. This ended up being a significant reduction compared to their baseline weights, but there was no significant difference between the two groups.

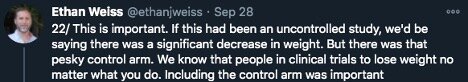

This non-significant difference between groups was somewhat unexpected for Dr. Ethan Weiss, the study’s principal investigator, who pointed out in his Twitter thread when detailing their findings:

“This is important. If this had been an uncontrolled study, we’d be saying there was a significant decrease in weight. But there was that pesky control arm. We know that people in clinical trials lose weight no matter what you do. Including the control arm was important.” – Weiss via Twitter.

About 50 participants underwent in-person testing to measure changes in weight, fat mass, lean mass, fasting insulin, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), estimated energy intake, total energy expenditure, and resting energy expenditure.

Within these secondary outcomes, there were no significant differences within or between groups, with the exception of lean mass.

The TRE group experienced a significant reduction in lean mass (compared to baseline), but the CMT group did not (though there was no significant difference between groups). The average weight loss in the in-person TRE cohort was 3.7 lbs, and approximately 65% (2.4 lbs) of this was lean mass. The authors report that ~20-30% lean mass loss is expected during weight loss, so a 65% finding is concerning. For anyone trying to lose weight, lean mass is not what we want to reduce; fat mass is.

The authors suggested a couple of reasons why this may have occurred. Either the TRE group consumed less overall protein than the CMT group or protein intake was equal, but the timing of protein intake made a difference. The latter would suggest an inherent disadvantage to the 12 pm to 8 pm eating window.

Increasing protein intake during weight loss (i.e., while in a caloric deficit) can help spare lean mass. Physical activity, and specifically resistance training, during weight loss, can, too. In this study, the TRE group had a significant reduction in daily movement and a significant decrease in step count. Not only would this have contributed to overall energy expenditure (and therefore weight loss), but reduced physical activity could have contributed to the loss of the lean mass.

All of this is to say that loss of lean mass can be prevented or significantly attenuated during weight loss by increasing protein intake and engaging in some form of exercise – two factors not controlled for in this study.

If you are currently practicing TRE, and are now concerned about your regimen, Grant Tinsley of Texas Tech University has shown in males and females that TRE paired with resistance training can lead to fat loss while maintaining and even increasing lean mass. So, if it is the case that there is something inherent to TRE that could be contributing to lean mass loss, exercise and protein can likely be used to circumvent this.

We could continue analyzing all of the reported results, but none of this means anything without considering adherence and study design.

Adherence

Peter Attia and his team took a deep dive into how this study reported adherence, which you can read about here. The bottom line was that it’s possible the adherence reported in the paper was inflated. Adherence was measured based on those that submitted responses within the app, therefore from those that were likely more engaged with the protocol. These results were used to represent adherence as a whole (100% of the participants). Of those that responded, 83.5% reported that they were indeed adhering to the TRE protocol. However, when you run the calculations, only 37% of the TRE participants actually responded to the question of whether they followed the recommendation or not. There is suspicion that this would not reflect the remaining 63% that failed to fill out their surveys.

Study Design

This study was an “Intention To Treat” study or ITT for short. This means that once randomized, participants could follow the recommendation or not, but their results are included in the analysis either way. In other words, you tell Sally to eat within the hours of 12 pm to 8 pm, but she eats from 8 am to 8 pm instead. Her weight is still included in the analysis. The purpose of this design is to see what happens when you give a patient a recommendation in a real-world scenario. Remember, these are free-living subjects. Weiss has made it clear that they were interested in seeing what happens to an overweight or obese individual’s weight when they are recommended to only eat between 12 pm to 8 pm, not whether they did it. This, in combination with the adherence issues, are incredibly important to understand when evaluating the outcome of any study, but particularly this study, because this is not clear within the paper’s conclusion. A result of a recommendation for a treatment is not the same as a result of following said treatment.

Regardless of these limitations, we are not surprised that merely telling an overweight or obese subject to eat as much as they want for 8-hours a day didn’t lead to meaningful weight loss or metabolic health improvements. No matter how long you fast within a day, what (food quality), and how much (caloric intake) you eat still matters. For all we know, they could have been eating Twinkies and hot dogs. When you’re opting for calorically dense foods that are easy to overeat (hyperpalatable/low satiety), 8-hours is still plenty of time to consume more calories than you need to lose weight.

If we take the study’s results for what they are, they suggest that TRE (16/8) alone is not enough to produce significant weight loss or improve other metabolic health markers. And suppose we assume that they maintained the diet that led to overweight/obesity. In that case, time does not appear to be a strong enough variable to control if improving weight and health is the goal. This contrasts with what’s reported in mice, where time restriction (without altering calories or diet quality) protects against the ill effects of an obesogenic diet. Future research should address diet quality when comparing the effects of TRE to a control similar to CMT.

It’s important to note that the reason TRE can be useful for weight loss is by supporting a caloric deficit. The advantage of TRE (probably much more likely when paired with a whole-foods based diet) is that this can happen without much conscious awareness for how much you are eating. The idea is that it’s easier to reduce time eating to reduce calories than to reduce calories with no reference for time (i.e., calorie counting). Because we don’t know what the participants were eating in either group, it is hard to make sense of the results, but that was not what this study was designed to test. It was designed to answer whether the recommendation to restrict food intake to a daily 8-hour window would lead to weight loss in overweight or obese individuals, compared to those who spaced out their meals over the day.

Where do we go from here?

Again, this study showed recommending TRE doesn’t lead to weight loss; it does not tell us whether TRE leads to weight loss. If you follow TRE and it’s working for you, we don’t see any reason to stop.

We are advocates of TRE; we use it ourselves and know several others that have found success using it. But, we also understand that TRE may not be the optimal tool for body composition changes. In other words, we realize that TRE is not a magic bullet. We are confident that stacking TRE with optimal protein + resistance exercise will equal impressive results for most. If your goal is weight loss and you don’t enjoy TRE and/or are finding success without it, then this approach is probably not for you. We realize many people like the freedom of eating smaller meals spaced throughout the entire day.

Although TRE is a form of food restriction, there is considerable freedom and logistical advantages to reducing the feeding window. It is quite liberating not to have to stop your day to have a meal or snack every 2 or 3 hrs, although some really enjoy (crave) this! Most people observed that hunger subsides considerably in the fasting window after a few weeks of practicing TRE. Also, people consistently report feeling more alert and energetic in the 4-6 hrs of fasting prior to entering the feeding window. Dom consistently reports that doing TRE just 2x/week improves his continuous glucose monitor (CGM) profile (Levels App), and that this correlates with enhanced focus and work productively on these days.

In summary, it is reasonable to say this is not the study that proves TRE is ineffective for weight loss and health improvements. So, don’t throw in the towel too soon. There is plenty more to explore, and we are only scratching the surface. If anything, this study teaches us to dig deeper into the scientific literature, understand protocols, and how these protocols influence the results before we change our lives based on what we read in a headline.

Written by: Kristi Storoschuk; Edited by: Dr. Dominic DAgostino, Dr. Csilla Ari Dagostino