A series of papers published in the journals Current Developments in Nutrition, Frontiers in Endocrinology, and Metabolites are beginning to shed light on a ketogenic diet-induced alteration in cardio-metabolic biomarkers that has come to be known as Lean Mass Hyper Responders (LMHR). LMHR are defined, technically, by a triad of three metabolic features: LDL cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol ≥ 80 mg/dl, and triglycerides (TG) ≤ 70 mg/dl on a low carbohydrate diet (LCD), often at the level of a ketogenic diet (KD). While no measure of ‘leanness’ is currently defined in the criteria for LMHR, the name itself derives from the empiric observation that this metabolic phenotype is specific to those that are lean and/or athletic. In other words, the typical LMHR has a higher than average level of fitness, high insulin sensitivity (low HbA1C), and otherwise ideal cardiometabolic biomarkers, excluding the astronomically high LDL-C, which is a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

So, let’s now dig into the data and hypotheses behind the LMHR observation. The first of the above-mentioned studies was an observational cohort study including 548 participants who were all on low-carbohydrate diets, with median intake of 20 g/d net carbs, and who were able to report lipid data (LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG) from before starting a low carb diet and while on a low carb diet. Some important findings from this study were that:

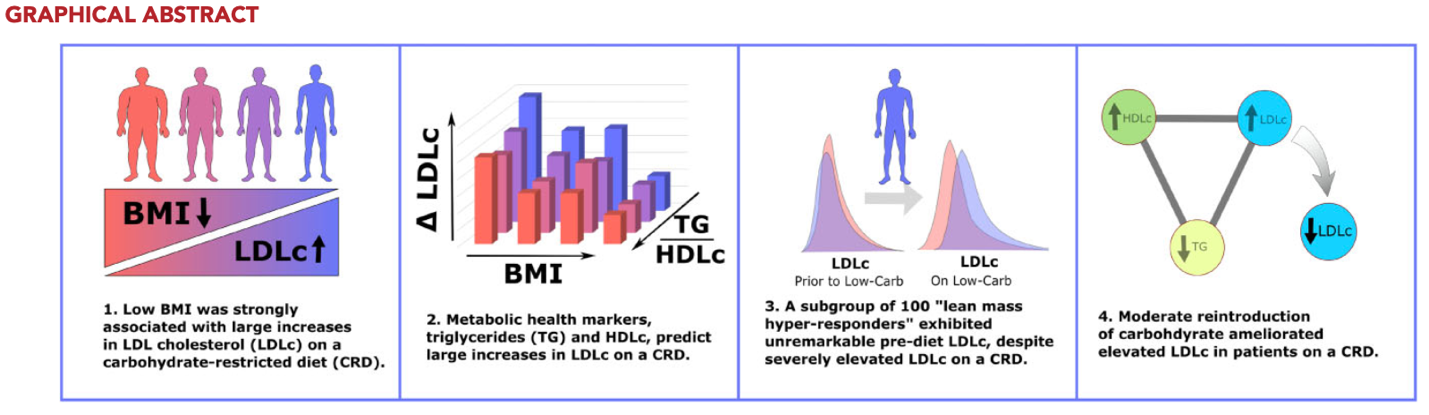

- BMI was strongly inversely associated with change in LDL-C when adopting a low-carbohydrate diet.

- TG-to-HDL-C ratio, a marker of metabolic health, was also inversely associated with change in LDL-C when adopting a low-carbohydrate diet.

- 100 of the 548 participants met all the criteria for LMHR, and these participants had lower BMIs as a group than non-LMHR.

- Mean LDL-C, HDL-C and TG levels in among LMHR were 320, 99, and 47 mg/dl, respectively; and this was despite LMHR exhibiting no difference from non-LMHR in terms of pre-low carb LDL-C levels.

- Finally, in an associated case report of 5 patients who underwent experimental carbohydrate re-introduction, adding back 50-100 grams of carbs was able to largely reverse the phenotype and lower LDL-C levels, in one case by as much as 480 mg/dl!

While these data are preliminary and certainly have their limitations, they are compelling. The authors used multiple complementary hypothesis-naïve methodological approaches, including regression models and machine learning decision trees, and the associations were consistent suggesting that lean (lower BMI) and metabolically healthy (TG/HDL= 0.5 to 1.0) are at greatest risk for LCD-induced increases in LDL-C, compared to persons with obesity, diabetes, or metabolic syndrome. This raises a number of questions: 1) what is the driver for LMHR phenotype? 2) what is the ASCVD risk? These are important questions considering that many LMHRs have adopted LCDs as a lifestyle for various health reasons, and KDs (and LCD variants) are prescribed for drug-resistant seizure disorders. Prospective studies to assess assessing plaque accumulation in LMHR are ongoing and will shed some light on this in years to come. and will likely be published

One explanation frequently posed for explaining the elevated LDL-C in LMHRs is overconsumption of saturated fat. However, in our opinion, this proposal may have several flaws. First, the order of magnitude increases in LDL-C reported in LMHR is beyond what one could expect from consumption of saturated fat. Eating lots of butter, cream, and fatty red meat might increase LDL-C by tens of mg/dl, but many LMHR exhibit increases of an order of magnitude greater, achieving LDL-C levels > 500 mg/dl. Second, saturated fat consumption doesn’t explain the triad that defines LMHR, including elevating HDL-C to 99 mg/dl, which was the average among LMHR in the prior study. Third, as there were inverse associations between BMI and LDL-C change and between TG-to-HDL-C ratio and LDL-C change in the prior study, invoking the saturated fat explanation would also imply that lean metabolically healthy people preferentially seek out higher saturated fat. This seems odd, but it is conceivable that LMHRs may have higher activity levels, causing them to seek foods higher in saturated fat to reverse a caloric deficit (very speculative). And, finally, not all LMHR consume diets rich in saturated fat. Given these observation it seems more likley that macronutrient composition (vs saturated fat) is the main driver of elevated LDL-C in LMHRs.

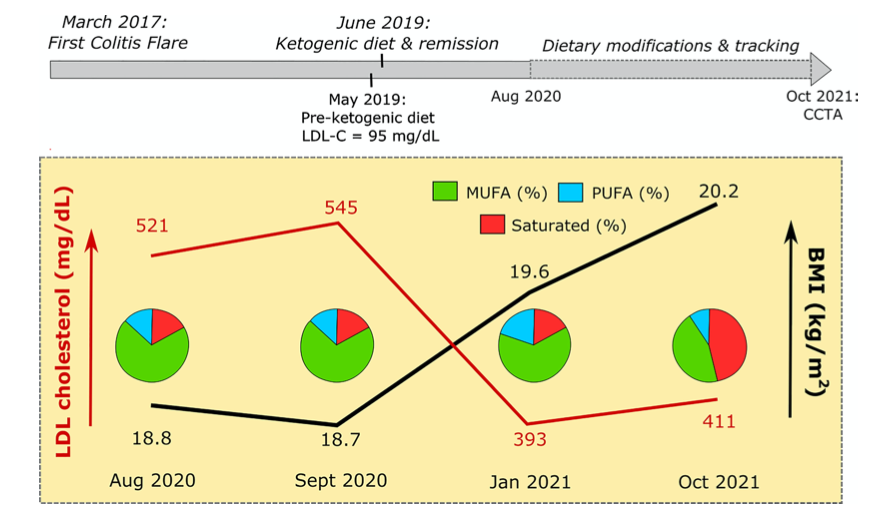

This, in fact, was the topic of a case report published in Frontiers in Endocrinology that covered the case of a LMHR who ate a ketogenic diet that contained as little as 15% of fat as saturated fatty acids, with the remaining 85% being made of unsaturated fatty acids from foods like olive oil and nuts. Nevertheless, this individual exhibited an increase in LDL-C from 95 to 545 mg/dl! What’s more, as the subject gained weight and his BMI increased, his LDL-C decreased despite an increase in saturated fat intake (video abstract: click here). While a case report should never be generalized to broader population, the comprehensive and rigorous manner in which this case was covered, including a genetic analysis, is at least consistent with the first observational study and the idea that there is more at play with LMHR than conventional explanation. In addition, there are anecdotal reports (we get many emails) of others eating LCDs primarily based on fish, eggs, nuts, olive oil, etc. and experiencing the same spike in LDL-C that was observed in this case report. KetoNutrition team member, Kristi Storoschuk, just nearly falls within the LMHR category (HDL: 85 mg/dL, TGs: 50 mg/dL, LDL: 189 mg/dL) while following a LCD, maintaining a lean physique, and no other risk factors for cardiometabolic disease. I personally also fall close to the LMHR category (HDL: 60-70 mg/dL, TGs: 40-70 mg/dL, LDL: 150-300 mg/dL) and have been urged to consider LDL lowering medication. Simply adjusting my daily carb intake from ketogenic (25-50g/day) to low carb (100-150g/day) lowers my LDL-C to within high-normal range (150mg/dL), but typically results in little or no ketones. I often bring ketones back up into the range (1.0-1.5 mM) with supplementation or time restricted feeding (TRF) when eating more carbs. Interestingly, adding some carbs back (independent of calories) resulted in my lowest fasting insulin numbers (2.6 to 3.3 µIU/mL). Maybe adding small amounts of carbs back in (50-125g of fibrous carbs) enhances insulin sensitivity and therefore lowers insulin over time? I suspect this could be the case, and it may lead to enhanced metabolic flexibility.

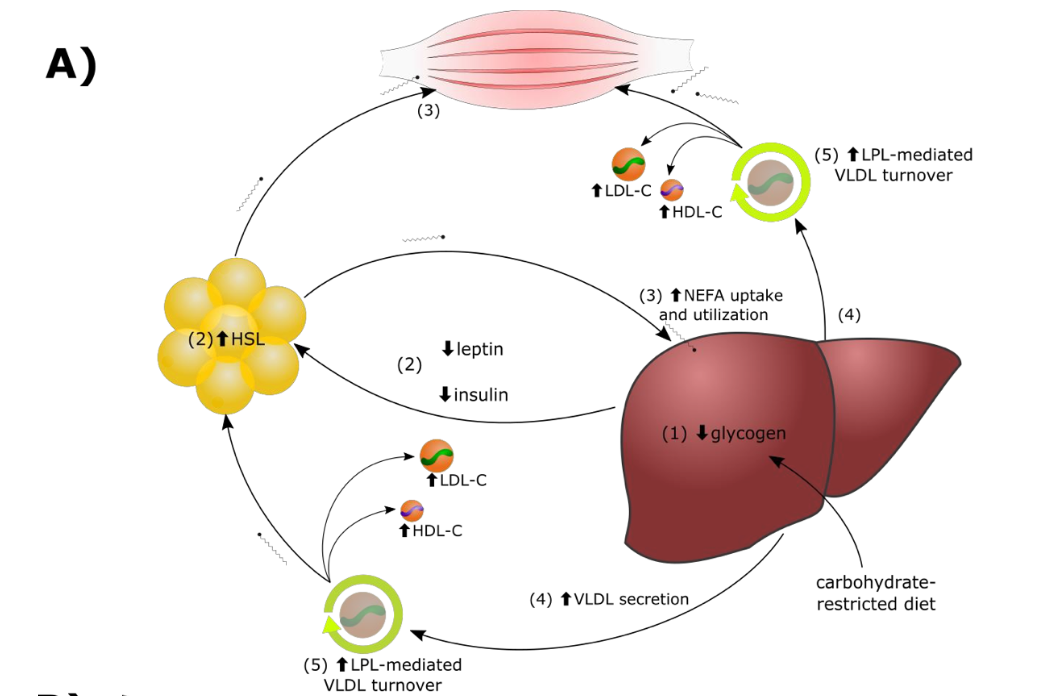

The third of the papers recently published was a hypothesis paper on the Lipid Energy Model, a mechanism that may explain the LMHR phenomenon and the relationships we are observing among carbohydrate restriction, BMI, metabolic health, and LDL-C change. The Lipid Energy posits that, with carbohydrate restriction in lean persons, the increased dependence on fat as a metabolic substrate drives increased secretion of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) by the liver and that these are then catabolized by lipoprotein lipase to generate marked elevations of LDL-C and HDL-C, and low TG. The model gets technical, but for a handy video explanation of the model, click here.

As mentioned, a prospective study is underway. This research will be essential to understanding the influence of elevated LDL-C on CVD risk in LMHR in the context of the otherwise metabolically healthy individual. At the moment, there is a strong case to be made for why in the absence of any other indicator of CVD risk, elevated LDL-C carries little risk, however, more research needs to be funded to test the current hypotheses. Until then, if you fall within this category, it is best to perform a more comprehensive lipid analysis (eg. NMR LipoProfile test) and other metrics of metabolic health, including blood pressure, inflammation, glucose control, to evaluate your overall health and CVD risk more comprehensively.

By: Kristi Storoschuk and Dr. Dominic D’Agostino