Muscle health is critical for metabolic health, and nothing improves and protects muscle health quite like exercise. Despite the overwhelming health benefits of exercise, it is clear that adults have a very difficult time adhering to regular physical activity. Unfortunately, the pandemic made these numbers even worse, with increased reported sedentary behaviors. The sad reality is that our modern lifestyles have engineered a day full of sitting and lack of movement, so unless we deliberately structure movement and exercise into our day, the chances are, the physical deconditioning is killing our cardiometabolic health.

Importantly, the number one cited barrier to exercise is time. As Hungarian-American physicist Albert-László Barabási once wrote, “Time is our most valuable non-renewable resource, and if we want to treat it with respect, we need to set priorities.” Most people reading this blog would agree that physical activity needs to be a top priority, and is highly correlated with optimal mental health and longevity.

The current physical activity guidelines recommend a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise per week to promote health and reduce the risk of cardiometabolic disease. Some people have no problem hitting or exceeding these recommendations, but for others, 30 minutes of exercise 5 days out of the week can be challenging

Is there a way to achieve the health benefits of exercise in less time?

Enter, HIIT.

HIIT, short for High-Intensity Interval Training is a form of exercise that involves repeated short bursts of vigorous exercise interspersed with periods of rest, or simply low-intensity movement – this is the “recovery” phase. The “work” interval should be around 80-95% (sub maximal) of your maximal heart rate. The simple way to estimate your max heart rate is to simply subtract your age from 220.

HIIT differs from other styles of exercise such as steady-state aerobic exercise carried out at moderate intensities for longer durations of time (think traditional cardio – going for a jog or continuous effort on a stationary bike). On the other end of the spectrum, HIIT differs from maximal effort exercise that can only be sustained for mere seconds, which would be the case with sprint interval training, or SIT. Depending on where you look, you might find different definitions of HIIT, and the protocols are numerous. This simple way to think of it is go, rest, go, where the “go” lasts anywhere from 20 seconds to 4 minutes or more, and the rest is of equal length or less.

It’s uncomfortable, but that’s just how HIIT works – usually the things in life that are most uncomfortable deliver the greatest benefits. What may get you hooked on high intensity exercise is when you start to notice those stairs you have to climb to get to your office floor get easier, or kicking a ball around with your kid isn’t as taxing on you as it once was. Daily living improves and becomes more enjoyable the more you can keep up, and HIIT can help with that. If your sport is bodybuilding or powerlifting, you will notice that HIIT dramatically enhances recovery (catching your breath) between sets, and will ultimately enhance training adaptations.

Example effective HIIT workouts (all effective; Dom prefers #1, 2)

- Two 20-second ‘all-out’ sprints done over 10 min (2x20s protocol; minimalist HIIT)

- Eight 20-second “all-out” sprints followed by 10 sec recovery done over 4 min (IE1 Tabata protocol; short, but very intense)

- 3 minutes off hard effort, 3 minutes of rest repeated five times

- 4 minutes of hard effort, 3 minutes of low intensity repeated four times

- 30-20-10 seconds increasing the intensity with each shorter interval repeated five times

- 20 minutes of 8 seconds of hard effort, followed by 12 seconds of rest

- 1 minute on, 1 minute off repeated ten times for 20 min.

- 4 minutes on, 1 minute rest repeated 5 times for 25 min.

You can choose any exercise that gets your heart rate up when performing HIIT. For example, on a bike, running, burpees, jump squats, mountain climbers, climbing stairs, etc. Even picking up the pace while lifting weights counts.

Note: Some people are scared of HIIT, thinking it’s “too intense” for them, but it’s all relative! There’s even research showing that picking up the pace while walking can be a form of interval training in older individuals, and can be a great place to start for exercise beginners.

Why we are interested in HIIT

The research of HIIT really hit the scene in the early 2000s with results from Martin Gibala’s studies at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. He claims he was only reinventing the wheel and that interval training was already being used by athletes, but this was the real academic emergence of interval training. The popularity of HIIT only increased when he appeared on the Tim Ferriss show back in 2017.

What’s amazing is that research shows that HIIT can provide similar, and sometimes greater cardiovascular, mitochondrial, and metabolic health benefits, compared to lower intensity exercise with a much shorter time commitment – all of which are associated with better health and longevity. This has both scientists, public health agencies, and health enthusiasts very excited because it adds more to the menu of exercise modalities and introduces the concept of time and intensity. Essentially, the greater the intensity, the less time you need to exercise for your health to benefit.

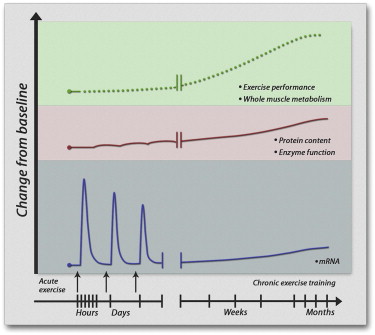

Many of the benefits of and adaptations to exercise are the result of how exercise “stresses” the body and our muscles. The transition from rest to exercise increases our muscle’s demand for energy, and therefore oxygen. In response, we start breathing heavier, our heart rate increases, and our blood vessels dilate to try and match oxygen delivery to the demand of our mitochondria inside our muscle cells. The way we get fitter and healthier is by adapting to this energetic stress induced by exercise so that we are better able to respond when the next bout of exercise rolls around. Our cardiovascular system gets better at delivering oxygen, and our mitochondria grow in size and number to get better at utilizing the oxygen. These major adaptations to exercise are responsible for the metabolic health and longevity benefits of exercise. It’s really important to understand that exercise extends far beyond any changes it makes to body composition or weight loss, rather it’s the metabolic response in our muscles that keep us healthy.

Source: Egan and Zierath, 2013

With endurance exercise, the longer you exercise, the greater you deplete muscle glycogen and therefore disturb the energetics of the muscle triggering these beneficial adaptations.

With HIIT, you’re not necessarily depleting fuels like you would be endurance exercise, but you are expediting this energetic stress response by exercising at a higher intensity.

Ok, but has HIIT been shown to improve the clinical markers of health we all care about?

Indeed, it has!

When scientists refer to fitness, they’re often referring to “VO2max” which is the maximal rate that our muscles can uptake oxygen and turns out to be a very important metric of health and independent risk factor of all-cause mortality. So, if you want to live a long life free of disease, having a higher VO2max is important. You can exercise regularly with a wide range of intensities to improve cardiovascular fitness, but the science of HIIT is showing that you can do it in less time. A 2015 systematic review found that HIIT resulted in greater increases in VO2max when compared to endurance training. HIIT appears to remodel our cardiovascular system to the same extent, and sometimes to an even greater extent, than traditional continuous exercise. HIIT has also been shown to be effective for fat loss, reduction in visceral adipose tissue (VAT), blood pressure, endothelial function, glycemic control, among other metabolic health benefits.

HIIT and blood sugar

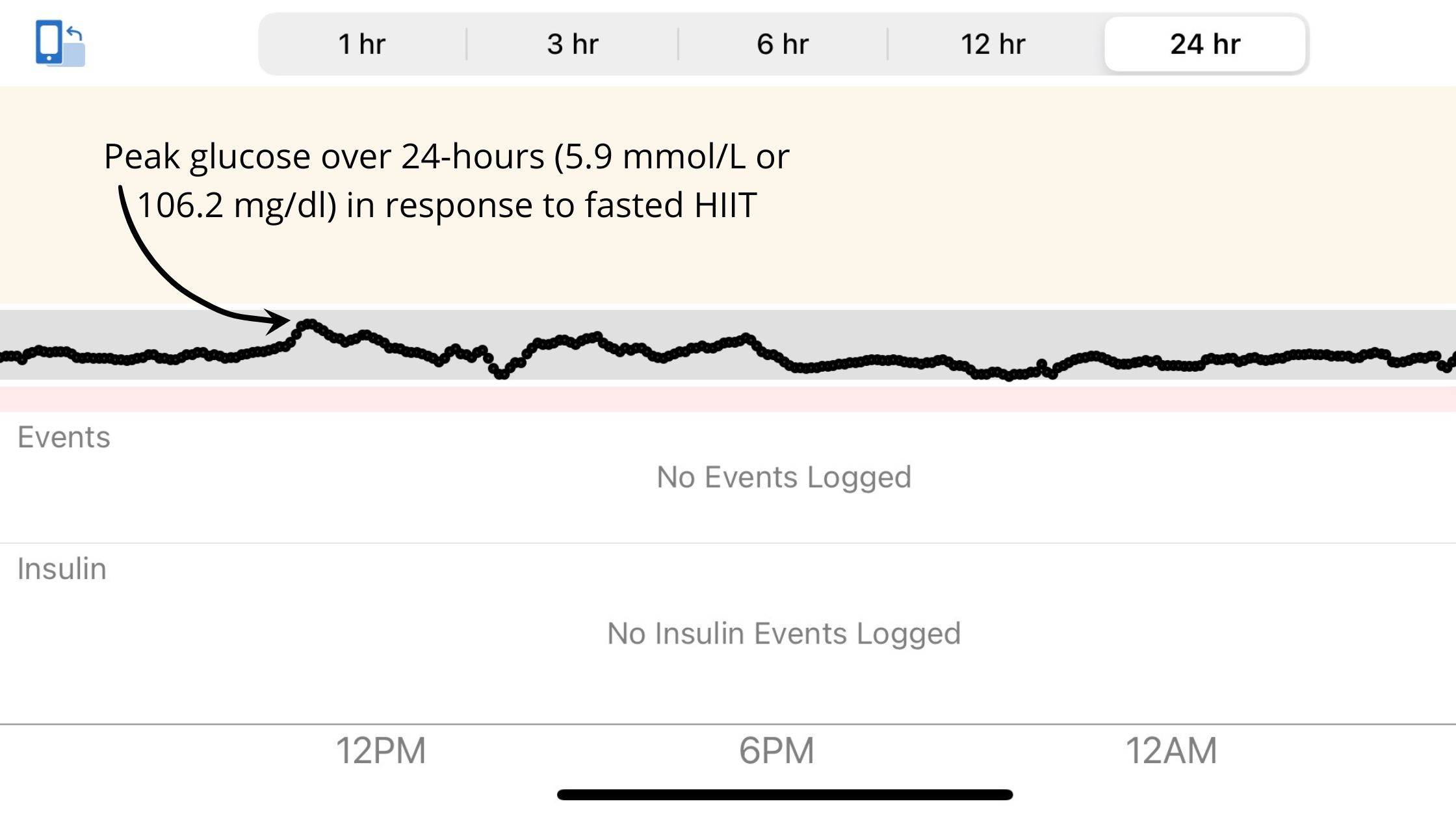

We all are probably aware that blood sugar is an important biomarker when assessing metabolic health, and physical activity is the best thing we can do to support our insulin sensitivity, and therefore blood sugar control. Acutely, high-intensity exercise can cause an increase in blood sugar levels, but this is nothing to be concerned about. This is simply your body responding to the increased rate of glucose oxidation (and hormonal response created by high-intensity exercise) in the muscles by releasing glucose from the liver to shuttle more glucose to the working muscles. The net result is improved insulin sensitivity and more stable (and lower) blood sugar levels. Studies show in individuals with impaired blood sugar levels, HIIT is an effective and time-efficient way to improve insulin sensitivity, glucose responses to meals, and 24-hour glucose levels. And when we say time-efficient, we mean it! The time commitment to see improvements in glucose control with HIIT is ~46% less than with moderate intensity continuous exercise.

Kristi’s glucose response to fasted HIIT in the context of a very low carbohydrate diet. This glucose is coming from her liver and is elevated because it is appearing in the blood stream at a pace that is exceeding uptake.

Any exercise is better than no exercise when it comes to improving insulin sensitivity and glucose control, but the growing body of evidence shows that HIIT is an alternative to moderate intensity endurance exercise, and may even produce greater benefits in shorter amounts of time. Even very low volume HIIT – 60 seconds of cycling at 90% max heart rate, with 60 seconds of rest between bouts, 3x per week for two weeks – improves insulin sensitivity and glucose control in type 2 diabetics.

HIIT, mitochondria, and metabolic flexibility

Muscle is the organ we care most about when it comes to metabolic flexibility, because muscle is the major site for both glucose disposal and fat metabolism. Healthy muscles have healthy mitochondria, and mitochondrial function is essential for metabolic flexibility. On the flip side, mitochondrial dysfunction is tightly linked to insulin resistance. Simply, the more mitochondria you have, the better you are at burning fuels, the better your endurance, and the lower your risk for developing type-2 diabetes and metabolic disease.

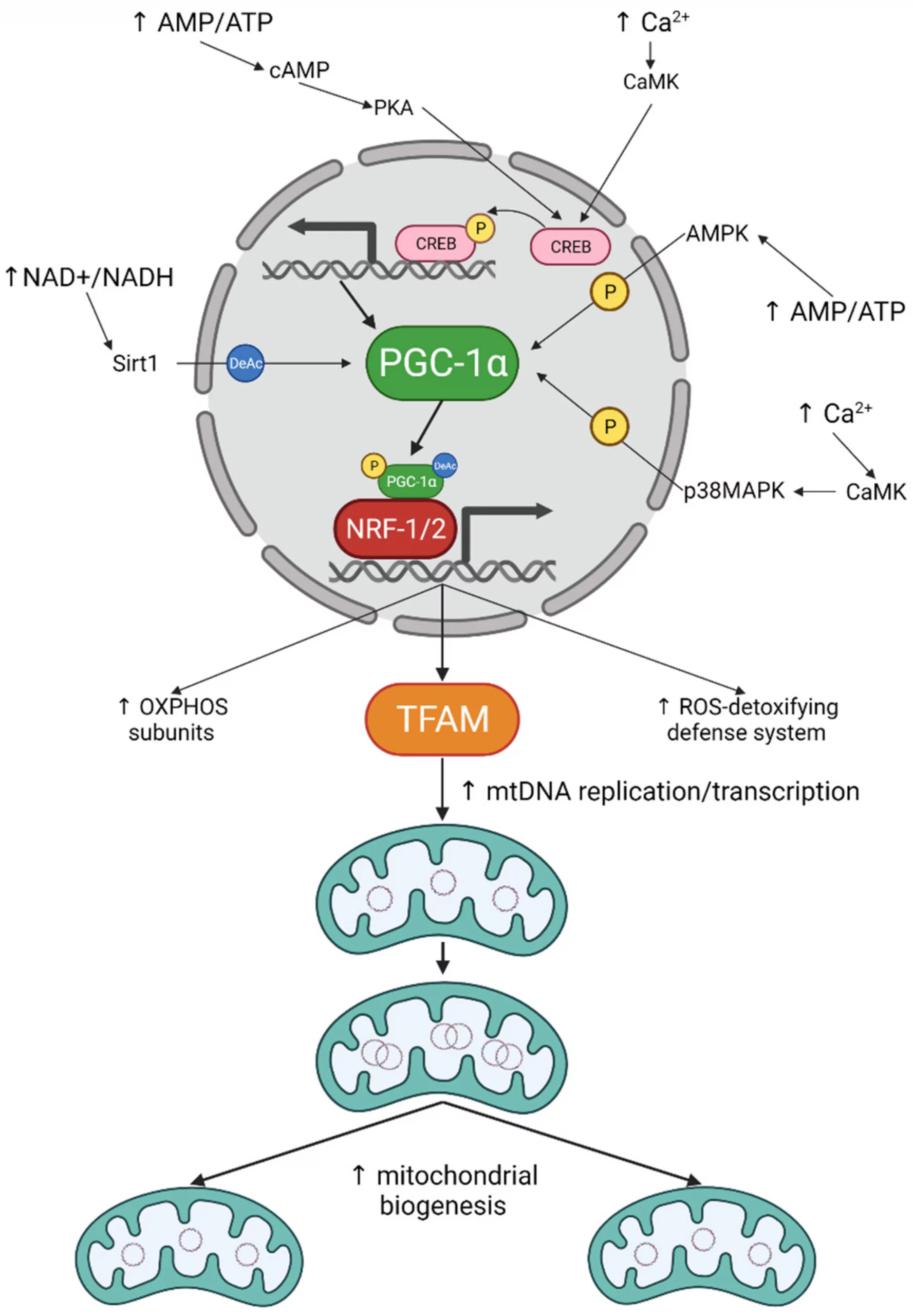

Energetic stress is the signal for the muscle to increase mitochondrial content and capacity, because upstream of mitochondrial biogenesis is the activation of AMPK. Due to the intense nature of HIIT, AMPK is activated causing the upregulation of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis (new mitochondria), like PGC1a. This was shown in the 2010 study by Little et al., where after only 6 HIIT sessions performed within 2-weeks led to increased PGC1a (the “master regulator” of mitochondrial biogenesis), other markers of increased mitochondrial content, and GLUT4 expression (the gene responsible for glucose uptake into muscles) – all of which are important for metabolic flexibility! The former makes us better fat burners, while the latter, better glucose users. In this particular study, the HIIT sessions consisted of 60 second intervals performed 8-12 times, separated by 75 seconds of rest. These findings have been replicated by other research groups, showing that HIIT is an effective training modality to improve mitochondrial function and fat metabolism.

Source: Cardanho-Ramos, 2021

HIIT in the context of low carb and fasting

If HIIT is highly glycolytic, meaning it’s glucose-fuelled, performing HIIT while fasted or in a carbohydrate depleted state doesn’t sound like a good idea. And it’s true, high intensity exercise performance can suffer while following a ketogenic diet, especially initially. However, assuming setting a HIIT performance record may not be your priority, HIIT is something to consider in the fasted or low carb state. For example, a recent study actually showed the two may synergize well in overweight individuals, where a very low carb diet in combination with HIIT led to improved body composition and fitness levels.

The research is very slim when it comes to fasted HIIT. One study showed 6-weeks of fasted compared to fed HIIT (60 seconds of cycling at 90% max HR x10) led to slightly greater increases in some markers of mitochondrial content and GLUT4 protein content but these differences were not statistically significant. This study was performed in overweight and obese women, and both fed and fasted HIIT led to improved body composition and metabolic health markers. The bottom line is that doing HIIT will produce results independent of diet or fasted state, but doing HIIT in a carb-depleted state may further augment the exercise-induced adaptive processes. We would caution against doing HIIT in a severe calorie deficit, since this stress would likely lead to reduced exercise recovery and greater muscle loss.

When first getting started with HIIT in the context of fasting or low carb, you may find it challenging. Over time however your body will likely adapt to performing at high intensities in these states, and HIIT will become more comfortable. We recommend supplementing with electrolytes, like LMNT, or ketone salts that deliver both ketones and electrolytes, to support exercise performance in the low glucose state.

Written by: Kristi Storoschuk and Dr. Dominic D`Agostino